/ Research

Colonial Troops in the First World War

Right from its beginning, the European colonies provided the First World War with a global dimension. Especially the use of colonial soldiers soon became a disputed issue and destabilized the racist and hierarchically defined relation between colonial masters and colonial 'others'.

On 28 June 1914, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne and his wife had become the victims of an assassination. While condolences were expressed from all over the world, a diplomatic tug of war began in the background of the seemingly quiet summer month of July. Supported by Germany, Austria-Hungary issued an inacceptable ultimatum to Serbia on 23 July. Only a few days later, on 28 July, the Austro-Hungarian declaration of war was followed by Russia’s general mobilization to support Serbia. On 1 August, Germany declared war on Russia, and within only few days, most European countries and Japan were in a state of war. During this phase, the war was formally a European one. However, in addition to the involvement of Japan, it was already during August 1914 that the European powers and their far-reaching colonial empires had transformed the conflict into a global war, including the deployment of troops from all parts of the world. This was especially true for Africa: in August 1914, the entire African continent – with the exception of Liberia and Ethiopia – was under the colonial rule of France, Great Britain, Belgium and Germany. Among the colonial powers Italy, Portugal, and Spain, which were initially not involved in the First World War, only Spain stayed neutral from 1914 until the end of the war.

The long prevailing view that the First World War was a European war, fought out at the Western Front in Belgium and France, which only developed into a global conflict in 1917, with the Russian Revolution and the United States’ entry into the war, failed to notice the colonial empires, and thus the global dimension that was inherent to this war ever since its first hour. The colonies played into the First World War in different ways: as war zones, as suppliers of raw materials and as pools of soldiers and workforce. The war, which had started as a local conflict on the Balkans in June 1914, was carried out in Togo, Cameroon, South Africa, German South-West Africa, and German East Africa, as well as at the Chinese coastline, in Micronesia, Samoa, and New Guinea already by August 1914. In addition to that, it was especially the Entente that incorporated the colonies into the wartime economies: between 1914 and 1920, the British colony of India contributed 146 million pounds to the British war expenditures and supplied the island with crucial wartime goods, such as cotton, jute, paper and wool. The French colonial power, for their part, received palm oil and peanuts from French West Africa.

It was, however, the use of colonial troops and workers from Africa and Asia at the West Front that radically and permanently changed the relationship between colonies and European colonial masters. For the support of its army behind the frontlines, Great Britain recruited roughly 330.000 civil workers from the Union of South Africa, since 1910 dominion and later (as of 1931) part of the Commonwealth, as well as from the colonies of the West Indies, Mauritius, the Fiji Islands, and Egypt. France made use of 185.000 non-European workers from Algeria, Indochina, Morocco, Tunisia and Madagascar.

Tirailleurs sénégalais in Verdun

Apart from workers without military status, like those Chinese men who were excavating trenches at the Western Front, the European powers mostly recruited colonial soldiers for the use on European territory, whose number is estimated to 650.000. While Great Britain recruited 1.5 million Indian soldiers, they only sent 150.000 to the Western Front (n.b. only during the first months), while the majority of these troops was used to fight the Ottoman Empire in Mesopotamia and the so-called German ‘Schutztruppen’ (‘Protection Force’) in East Africa. The French colonial soldiers received more attention, as they were an integral part of the French army in the régiments mixtes. From October 1914 until the armistice in 1918, more than 440.000 soldiers from Western Africa – some of them forcefully recruited – as well as several closed contingents from Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia – usually soldiers who were only 16 years old – fought at well remembered war zones, such as Ypres, the Marne River, the Somme River and in Verdun, following the motto “mort pour la France”. The Senegalese infantry tirailleurs sénégalais became especially famous.

The use of colonial soldiers was a disputed issue among the military powers and the Allies. France dispatched colonial soldiers to the European mainland, even though they were not allowed to shoot at members of the German Reichswehr. Besides their use in the war zones, many colonial soldiers were also used for forced labor in French factories that were vital for the war efforts. After a few weeks, Great Britain abstained from the use of such troops on the European mainland. Winston Churchill, back then First Lord of the Admiralty, and the War Office advocated the shipment of British colonial soldiers overseas; the Colonial Office, however, withheld its approval. The reason was that they had concerns whether the Indian troop units would be able to deal with the climatic conditions. Beyond these superficial worries, there were concerns about the possibility to maintain the existing military chains of command: in January 1916, The Times reports that the use of colonial soldiers made communication among the soldiers difficult. As an example, the paper refers to a battle in Cameroon, where British and French colonial soldiers fought side by side, while they were hardly able to understand each other, as the African soldiers did not speak English. This led to misunderstandings and problems during the military offensive.

Source: The Times.

Virtue or “Humiliation”?

In the same issue from January 1916, The Times writes about an official report by the French military leadership about “the great offensive of the Western front, known as the Battle of Champagne, of September 24, 1915, and the following days”. The Times attributed the result of the battle, which the Entente regarded as a severe defeat of the German army, to the French soldiers’ virtues and their readiness to combat, to “the incomparable individual worth of the French solder” (The Times, 1 January 1916, p. 4).While it was celebrated as the triumph of French values and a national willingness to make sacrifices by the Entente, the Oberste Heeresleitung (i.e. the Supreme Army Command) of the German Reich interpreted the events quite differently. A photograph of French prisoners of war, which was published one year later, shows two African soldiers, presumably from French Guinea. The photograph came from the Bild- und Film-Amt, the German department responsible for propaganda through images and photographs since1917, and it had the title “Einige Typen der ‘Kulturträger’ der Entente aus den letzten Kämpfen in der Champagne. Kämpfer aus Neu-Guinea” (“Several Types of the ‘Culture Carriers’ of the Entente from the Last Fights of Champagne. Fighters from New Guinea”). A closer look reveals that the Bild- und Film-Amt’s description of the image is flawed, as the photograph’s handwritten attribution on the front side of the image, the soldiers’ uniforms, as well as the circumstances clearly indicate that the two men were tirailleurs sénégalais from the French colonies in Western Africa.

The use of colonial soldiers escalated within a short time and became a disputed issue, which blurred the boundaries – to remain in the language of the time – between culture, civilization and barbarity that had been clearly drawn by the European colonial powers until 1914. Through the presence of those colonial ‘others’, the racist and hierarchically defined relation between European colonial masters and colonial ‘others’ was destabilized at the Western Front.

From a military perspective, the use of colonial soldiers was less relevant than it was for the relation between the colonies and the European colonial masters. Never before had a migration movement with such a large number of people from Africa and Asia occurred, and rarely before had the inhabitants of the colonies had the possibility to come to Europe to get a first-hand impression of European societies. Especially the Central Powers knew how to make use of these deployments for their propaganda efforts: in April 1915, The Times reports in a sort of press review on how different German media presented the prevailing perception that the Allies would not have been able to face the German Reichswehr without the use of colonial soldiers (The Times London, 27 April 1915).

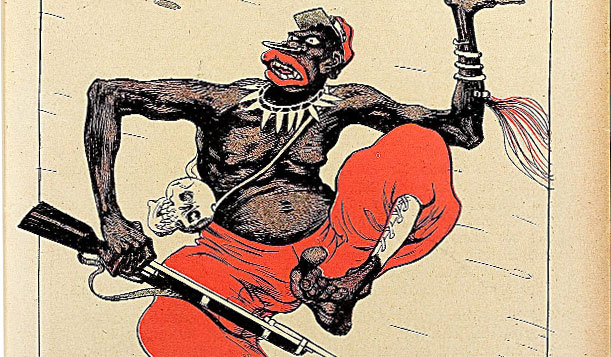

This report was based on the topos of the superiority of European civilization that was well-maintained by the German propaganda; a superiority that was to be protected against the rest of the world, even during the war. In Germany, the use of colonial troops was considered as the breaking of a taboo: the satirical newspaper Kladderadatsch wrote of a “häuslicher Streit” (“domestic argument”) among white “Brudervölker” (“brother peoples”), which was wrongfully decided by the deployment of “Kolonialvölker” (“colonial peoples”). Especially the French colonial soldiers were described as “wilde Menschenfresser und blutrünstige Bestien” (“wild man-eaters and blood-thirsty beasts”) by Kladderadatsch. Under the headline “Die Zivilisierung Europas” (“The Civilization of Europe”), which is complemented by a drawing on the cover page that depicted a tirailleur sénégalais with all the known racist stereotypes of the time – a naked torso, a nose ring, big lips, hands and feet, as well as a skull hanging around his neck – the magazine evoked the fall of Europe. The use of these troops opened the door to barbarity in Europe, because it allowed African soldiers to enter; and the Kladderadatsch regarded most of them as inferior people (Kladderadatsch, 23 July 1916). The actual barbarity, according to the tenor of the contribution, were not the German war crimes – these were not even acknowledged by the magazine –, but the support of European armies within Europe by colonial people, which in consequence was understood as the termination of a kind of solidarity between the ‘white’, ‘civilized’ nations of Europe. In that sense, the Berliner Tageblatt referred to the colonial soldiers as “schwarze Schmach” (“black humiliation”) or “brutale Wilde” (“brute savages”), who committed countless acts of violence against German women and children – the German propaganda and the Supreme Army Command had, however, difficulties to appropriate suitable proof for those accusations (Berliner Tageblatt, 18 March 1915).

Sources: Kladderadatsch; Berliner Tageblatt; The Times.

Colonial Soldiers in Paris and Algerian cyclists à la campagne

The army commands of France and Great Britain tried to provide counter-propaganda in order to weaken the topos of the rupture in civilization and to calm their own population’s fears caused by the armament of African soldiers and their presence in French cities as free citizens.

This counter-propaganda included the distribution of photographs depicting scenes from everyday life, such as wounded colonial soldiers who were accompanied by French military personnel in the streets of Paris, or propaganda films, like the one from 1915, where the Fourth Regiment of the tirailleurs tunésien orderly moved into their camp in a French village – led by a row of Algerian soldiers pushing their bikes.

» Watch the film: Défilé du 4e régiment de tirailleurs dans un village: nouba, prise d’armes sur la place, exercice d’assaut, fête et danse de l’« homme-cheval », numéros de jonglage avec fusil, scènes burlesques et jeu du sabre. Europeana 1914-1918. Even though the film title identifies them as tirailleurs algériens, the depicted colonial troops are from Tunisia.

The deployment of colonial soldiers and the fierce disputes about its effects on the self-perception of European publics and on how the colonies would regard their colonial masters had severe consequences for European societies. Even though colonial soldiers constituted only a fractional part of the estimated 70 million armed people of the First World War, the experiences of such a brutal conflict, carried out among European societies that were convinced about their racial and civilizing superiority, shattered precisely this claim of being an advanced civilization.

A vivid example of the growing self-consciousness of the colonies during and because of the First World War is provided by the service record book of an Algerian soldier who served between 1914 and 1919, first in France for the first regiment de zouaves, later for the third regiment mixte zouaves et tirailleurs in Verdun and other places. Besides the usual information on person and military rank, the service record book also includes letters of recommendation, emphasizing his courage, his responsibility and his devotedness. The cover page of the service record book is especially noteworthy: it includes a photograph of the obviously proud Benito Perès, standing in front of a balustrade, dressed in the attire of the tirailleurs algériens, and surrounded by foliage and a banderole with the slogan “Honneur, Patrie, 1ème R de Zouvas”. The background illustration is telling as well: it depicts a scene from the French countryside: several houses can be seen in the background. In the foreground, there are trees, and in between them, armed tirailleurs carefully leave their coverage to approach the village.

Colonial independence movements during the 1920s, such as the demands of the Indian National Congress for independence from Great Britain, were also influenced by these unique experiences from the First World War. Verdun or the battles at the Somme and Marne Rivers had questioned the integrity of the colonial masters and fundamentally destabilized Europe’s self-perception as a role model and an epitome of civilizing progress. In return, the colonial soldiers did not fail to have an effect on the French, British or German societies. The sudden presence of black soldiers in the French countryside or the country’s capital Paris, as well as the necessity to provide the Africans with supplies and to welcome them as “comrades-in-arms” quite clearly demonstrated to the European colonial societies that their global supremacy was precarious and transitory in its nature.

Naoual Astitouh, Cornelia Knab, Manuel Knapp, Isabella Löhr

Illustrations:

- A tirailleur sénégalais at a French railway station in 1914. Image Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. [JPEG] (JPG, 107.59 KB)

- „Im Westen, farbige Kriegsgefangene aus Neu-Guinea“ ("In the West, colored prisoners of war from New Guinea"). Image Source: Deutsches Bundesarchiv, Wikimedia Commons. [JPEG] (JPG, 69.42 KB)

- Cover page of the satirical magazine Kladderadatsch from 23 Juli 1916. Image Source: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg. [JPEG] (JPG, 231.12 KB)

- “Turcos, wounded at Charleroi, in Paris“. Image Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. [JPEG] (JPG, 130.40 KB)

- Service record book of an Algerian soldier. Image Source: Europeana 1914-1918. [JPEG] (JPG, 275.46 KB)